Features

Please click on the panels below to read intersting snippets from our archives.

Visiting Snr Luzzi

We have just come back from a fantastic week in Tuscany. We stayed in a farmhouse and had a hire car. As usual I had reasons other than the scenery to visit Italy

Looking at the map on the first day, Firenze to Bologna did not look too far, the Autostrada looked nice and twisty with plenty of tunnels. We went to Bologna a couple of years ago to visit the Ducati factory but did not have time to go into the centre. This time the plan was to look for a Tourist Info office in the centre and ask if they knew the location of the old Morini factory.

Even on a Sunday the traffic was horrific. We made it to the centre but could not find anywhere to park, there are endless narrow one way streets, everytime I wanted to turn in a certain direction the roads had a no entry sign. We went round in circles for hours. We ended up stopping wherever we found a gap at the side of the road for just a few minutes and walking round.

There are two very old and tall towers in the centre next to each other, one of them leans more than the one in Pisa, very spectacular, it will make a very big mess when it falls over! We could not find a tourist office nor could I remember the name of the road to ask for directions to the factory. After several hours we gave up and tried to find a way out of the city. I had heard that the factory was hard to find and now having been there I know why. As we went down the slip road onto the motorway to go back, we saw the Franco Morini factory over our right shoulders, which looked to be quite a large site.

A couple of days later we went to Sienna. Might as well try to find Cesare Luzzi's shop while I'm here. This time we had a map and very quickly found Via Piave. We parked about ten minutes walk away. Towards the bottom of the hill Suzanne saw an Excalibur through a window at foot level. At the bottom was a small set of glass doors opening out into a triangular shaped workshop. The doors were wide open but no one was to be seen. Near the doors were a couple of old Corsarinos, further in a 350, a couple of 350 engines were on a workbench, all the workshop tools were hanging on the walls. At the end were a couple of single cylinder engines (Settebellos possibly?) on another bench. A Corsarino scrambler was on a hydraulic lift in the centre. Everywhere around the workshop were boxes and piles of Morini parts.

We stood and looked around for about ten minutes, still no-one to be seen. Just as we were thinking of leaving, a van pulled up and an oldish gentleman got out and came into the workshop. 'Snr Luzzi ?' I asked. 'Non' he replied and pointed back at the van just as a very old looking gentleman came around the corner. He had blue overalls on and was almost bent in half. We guessed he was around 80 years old. I said hello and tried to explain who I was in my best, not very good Italian. 'non capisco' he said in his old voice and turned around and walked out.

Suzanne and I looked at each other as if to say what the hell do we do now, then Snr Luzzi came back into the workshop and beckoned us to follow him. He went over the road and in through another glass door into a dimly lit shop. This one was more of a showroom, crammed full of Morinis. There right in front of the door was THE 250 GP Morini.

Snr Luzzi saw the look on my face and grinned, I think he had forgotten his false teeth that day. I couldn't understand everything he said, sometimes very old men speaking in English are hard enough to understand, but I heard Provini and Agostini and he said the bike should have a fairing on. The bike looked just like it had been parked up after it's last race and not touched since. It was battle scarred and covered in oil and incredibly small.

Then he asked me something and I just made out the word 'ricambi' - spare parts, I nodded. I wanted a kick starter 'avviamento' mine has a bad crack in it and a side panel badge to replace the one lying at the side of a French road somewhere south of Paris.

He spoke no English at all and is also slightly deaf but by pointing at parts on other bikes and with the few Italian words I know we sort of understood each other.

He said there were no spares in his workshop and they were kept 8 kilometres away. The kickstarter he said was no problem, even the later K2 style one I wanted, the side panel badges he tutted and said 'un pocco', only a few. Then he asked where our car was. 'About 10 minutes walk away'

He shook his head and then beckoned us to follow him again. He opened up a Fiat Uno and indicated we were to get in.

Was this a good idea?

We were sat in a car with an 80 (at least) year old Italian who had no teeth, was slightly deaf, spoke no English, walked with a stoop. Was his eyesight any good? We had no idea where he was going to take us, only that it was 'otto kilometri' away. What were we thinking of.

Five minutes into the journey, he patted his pockets and banged his fist on his forehead, 'chiave', he'd forgotten the keys to wherever we were going.

Back to the workshop to get the keys, when he got out we were thinking of doing the same and making a run for it.

As it turned out he was a very careful driver and took us around Sienna and off into the countryside and up into the hills. All the time he was driving he only ever used one hand on the steering wheel.

He said he spoke no English but that his son lived in America and spoke very good English. On the way there we did not speak much, but he seemed to be getting more friendly and less abrupt.

Eventually we came to a stop outside a two storey barn. Snr Luzzi pointed to it and said it was going to be a Morini museum one day and that the building was 1000 years old. He opened the gates and went towards a second barn. All around outside were Morini parts, mudguards, tanks, sidepanels, a box of crankshafts. He uncovered one crate which was full of unmachined crankshaft castings. Then another where he showed me two more finished cranks with con rods, one a very early 350 one.

Inside the second barn was full of racking. An Alladins cave full of Morini bits.

He disappeared off into the depths and came back a few minutes later with a kick starter, he was shaking his head and looked for another parts book. It was an earlier kick starter to the one I wanted. He knew exactly which type I wanted and was very disappointed to find he did not have one. I think he swore a few times in Italian then was very apologetic for not having what I needed.

Off he disappeared again and came back with a side panel badge, in Silver, not Gold. That was all there is left. He also gave me a couple of 500 Camel stickers in gold and indicated I could cut the 'Camel' part off.

He gave us a quick guided tour. I remember seeing dozens of seats in plastic wrapping, boxes full of A,B and C cambelts, cables, gaskets, camshafts and lots more I have forgotten.

I felt guilty for bringing him all this way for just a 500 badge and tried to think what other parts I wanted. Seeing all those spares just made my mind go blank. Then I remembered I could do with a new headlamp shell, mine has cracked and been welded several times. Off he went again and came back with a complete headlight unit, including bulb, in a plastic wrapper.

Thankyou.

I asked if I could take some photos, but as he replied he turned away and walked outside again beckoning us to follow. I didn't understand his reply and was reluctant to take any photos in case he had said no. He was turning into such a sweet old gentleman I did not want to risk insulting him.

We went around the back of the barn and up some steps to the upper floor. He unlocked the door and with a big grin let me go in first. More of the same, the entire floor was covered in piles of Morini Spares with more racks at the far end. Then he pointed towards a ladder going up into the roof space and told me to climb up. Again it was full of plastic body parts, petrol tanks, exhausts.

While I was up the ladder, Suzanne said I was in 'paradiso', Snr Luzzi took hold of her arm and giggled like a small child.

On the second floor I picked up an unmachined piston casting out of a small pile of them, Snr Luzzi just grinned and nodded again.

He picked up a large Bing carburettor as fitted to BMWs and said it was from the last Morini, I'm sure he said a 750. Then he picked up a brand new Ducati 900 cylinder head to show me.

On the way back he was a lot more talkative. He said he started at Morini on the 6th of January 1952 and before that had worked in Germany. He also said 1910 in Italian. I'm sure he was talking about when he was born. That would make him 91 years old!

I think he had also had a bad accident and was in a plaster cast from his waist to his neck for several months.

I mentioned Franco Morini, and he said that in his opinion they would never make a full sized motorbike, they were only interested in Scooters, scooters, scooters. he banged his fist on the dashboard each time he said the word.

Everytime he talked to me he would take hold of my arm with the one hand he was steering with and lean over to me. It was very hard for me not to grab hold of the steering wheel and bring the car back into the right side of the road each time.

Back in his showroom I asked if I could take some photos of the GP bike. 'of course' he said. As I was doing so he tapped me on the back and pointed towards the back of the showroom. 'tre e mezzo prototipo'.

It was very hard to see because the bikes were so close together but there it was. It was definitely a 350 Strada, but all the details as we know them were slightly different. The rocker covers were curved towards the front of the engine, not flat, and the ignition switch was down near the oil filler. He said it was made on the 29th of November 1969.

I barely had time to look at it when he pulled me towards a factory Settebello 175 racer and told me to photograph that. Then we went into a back room and down some stairs. There were even more older Morinis down here, again tightly packed in and hard to get to. He went over to one of the Works Regolarita machines and patted the tank proudly.

His love of these bikes was obvious and I could tell he was very proud and excited to be able to share them with someone who also felt the same way.

I offered him some money towards his petrol. 'benzina??' he said in amazement, 'no,no, no' and flatly refused anything for his time and petrol costs.

He wrote down the cost of my headlamp and badges on a scrap of paper, I was 10,000 lira short in my wallet and asked Suzanne if she had a 10,000 note. Snr Luzzi said not to worry and accepted what was in my hand. When Suzanne took out a note he refused it.

I wanted to shake his hand as we were leaving but he said his hands were dirty, I insisted anyway and we shook hands.

This lovely, dear old man might have possibly helped to make my bike, or handled some of the parts before they were fitted, or even just seen it in the factory.

And I shook his hand.

I apologised for my bad Italian, this just made him grin more and shake my hand harder. I wish I could have asked him so many more questions.

Suzanne also went to shake hands and he took hold of hers, bent over even further, and kissed the back of it.

He wished us 'bon fortuna' and waved as we walked back up the hill.

Back in England, we both agreed that the highlight of our holiday had not been Sienna or San Gimignano or Pisa or Firenze, but our time with Snr Cesare Luzzi, a lovely old man.

(Snr Luzzi sadly passed away in November 2004)

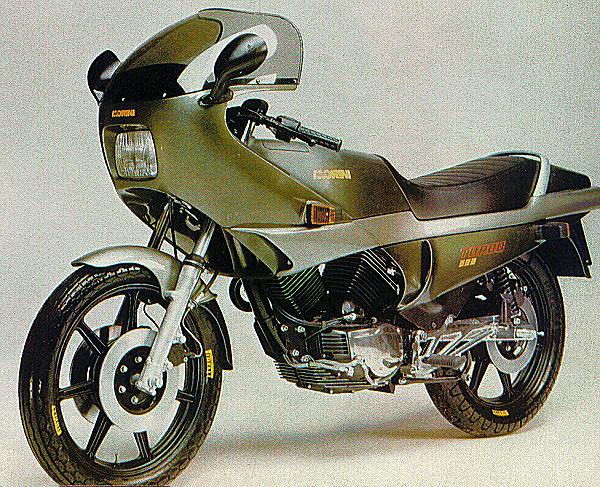

Darting around the Dolomites, Tom Farrow

Firstly a huge thank you to everyone who gave me some suggestions as to how to rectify my Dart's erratic behaviour a few weeks ago. The solution came in the form of a hideous, restricting plastikky piece of junk from the airbox that was missing (it had rolled under Dads '49 Meteor when we changed the aircleaner), thereby causing the bike to breathe freely for the first time in it's life! Of course, the emissions regulations which affect the Dart call for all this strangulation (and of course re-jetting) but given the bikes scrooge-like fuel consumption on a recent trip, I don't know why it needs it…

It's summer 2001. The sun is shining and I'm happy. Happy because in a week's time I will embark on a journey of discovery, fun and, of course German Weissbier! The plan was to ride from home in London on the Dart, with Dad on his '49 Vincent Rapide, and his mate Andy on a '51 version, through France, Germany, Austria and finally into Morini land, for a few days blasting around the Italian Dolomites.

I've never driven on the wrong side of the road(well not intentionally anyway!) and the longest journey I'd ever done on a bike up till that point was London to Brighton on the Dart a couple of weeks earlier. On top of which, I've only had my full bike license for a couple of months and the Dart has been on the road for only a few weeks. This is a big test for both machine and 18 year old me.

We left home for what was supposed to be a fairly un-eventful journey through France with an overnight stop in Reims. Once in Calais and out of reach of those speed camera-wielding maniacs they call the police, I felt it was time to play my part in the "genuine 100mph Morini" debate. A nice open stretch of motorway… I looked down at the speedo. Crikey, Morinis don't go that fast do they?? Speedo can't be working properly. 175? Naah. Sure enough though, quick stop for petrol and…

"Bloody hell Tom, we were going a bit quick there weren't we?"

"Er, no dad, I don't think so. Maybe 80mph…"

"Well the speedo on my Vincent was reading 110."

Damn, rumbled. "Okay Dad, we'll take it a little slower now". For the sake of the Vincent, obviously!

We reached Reims at 8pm, but there was no accommodation to be had after a 2-hour search. It never used to be like this in France - be warned! So it was fill up with fuel and press on. At 12:00 we slipped into a service station to fill up with Coffee and to see if we could find a half-comfy chair for a nap. The chairs were uncomfortable, and our attention became fixed on the far-fetched film playing on French TV. Despite having about a 5-word vocabulary in the language, we got the gist fairly well. To our horror, we discovered that satellite News channels don't show films. It was September 11th.

Back on the road,somewhat subdued, and in desperate need of a bed for the night. Ah ye of little faith - a "Formula 1" room was procured at 2:45 am for 140FF (£13) and we all piled in for a most comfortable sleep.

On Wednesday morning, we headed off for another stretch of motorway. The next two days would be pretty repetitive; Motorway, petrol station, sleep etc, but riding past Lake Constance was good, and made a nice change to the fairly boring motorway sections.

Friday should have been an omen. The glorious sunshine had been replaced with dull skies and damp roads. Waterproofs on, we finally set off from the luxurious Hotel Maximillian in Reutte, Austria at about lunchtime. Maybe the weather would clear once we reached Italy. Or maybe not. As we neared the border, the rain came down heavier and heavier. Our (not so) waterproofs were clearly no match for the heavens and so after paying several thousand Lira for a squirt of fuel, we stopped in the worlds smallest motorway service station café to dry ourselves. Off with the gloves, boots socks. Ring out the water and leave to drip-dry. By the time we left it was the world's first motorway service station swimming pool!

Back to the bikes. By this time we had been joined by Michael Jackson on a 1970 Honda 750 four. Interestingly this bike struggled against the Vincents let alone my Dart. Maybe the Honda was jealous of just how competently the Dart was performing on only two cylinders, but anyway for some reason when we left the service station, his bike was now a 375 two. Off we went. Cautiously. The Brenner Pass is an elevated stretch of motorway and is exposed to some quite strong winds. Add to this the numerous 90 degree bends, persistent rain and crazy lorry drivers, intent on travelling far too fast for the conditions and what you get is a recipe for disaster. It nearly ended that way too. Coming out of a long tunnel and the road suddenly turned left. Andy, a walking mountain of a man hit a slippery bit in the road and had a job wrestling his sideways Vin round the corner. The rest of us got round it. Just.

Our refuge in the Dolomites was located 2,250m up (Ref. Carlo Valentini - Passo di Sella), in the middle of a network of small twisties with hairpin bends and dodgy cambers. Fantastic Morini-ing roads, I know, but I was not looking forward to them. It wasn't the corners I was worried about, nor was it the pathetic 2 foot wall which "prevents" you from plummeting several hundred metres off the side of a mountain. It was the fact that, contrary to our hope that maybe the refuge was above the rain clouds, as we ascended the mountain, the rain got heavier and heavier, then much colder.

By now, Dad was miles behind, shepherding the mis-firing and poor handling Honda of Michael, whilst Andy was miles in front of me, confidently slinging his Vin around whichever kind of bend the Dolomites threw at him. I didn't expect to keep up, after all I had come on this trip to learn and get used to the bike. However, I also didn't expect what came next.

The rain turned to hail, then snow. My visor began to ice up, and despite how much I love my bike, for the first time ever, I'd have done anything to swap it for a car (or a snowplough for that matter!) Feeling as if I had been transported into a Hollywood film set, so sudden was the change in weather, I gingerly proceeded up the mountain. For the first time in my life, 10mph felt too fast!

As I rounded a particularly slippery 180 degree bend, the most enormously steep hill I had ever seen lay in front of me. I was tempted to stop there and then, but a tyre trail, already almost completely filled in by new snow, indicated that Andy was not far ahead. I took a deep breath and eased my way up the hill. As I reached the top, feeling enormously proud that I'd managed not to drop the bike, an unmistakable red Vincent came the other way…

"We're going the wrong way, we'll have to go back down," said Andy.

"You're having a bloody laugh." I could have killed someone.

"It's not so bad, just use your feet as skis and try not to use the brakes or you'll lock the wheels…"

"Thanks Andy, wish I had your optimism. How exactly are we supposed to stop without braking then?"

We eventually managed to reach the bottom of the hill and met Dad and Michael coming up. A short ride up a tiny side road we'd missed (skate down the 30-degree incline - fortunately helped by two well thawed out chaps) saw us parked safely just outside the refuge's garage, which was already full of bikes whose riders had the pleasures of arriving before the snow came.

Twenty minutes in the boiler house at the refuge and I could once again feel my hands and feet. I wasn't going to repeat that journey in a hurry. As it turned out, nobody would. Snowed in for two days, -6 outside and nothing to do except talk about how good the roads normally are in the Dolomites and drink copious amounts of beer and wine. Shame! Riders from UK, Holland, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy and even the USA were in attendance at this little end of season bash of the Vincent club. There were many interesting tales and everybody was interested in the Morini.

Coming up that mountain, I may have been absolutely petrified, but there was no way I could fault the Dart. I'd ridden in sunshine, Rain and Snow, almost non-stop on the motorway for 3 days; 1,600Km without missing a single beat! I have to admit I wasn't expecting that, especially after the problems, which we cured only 2 days before setting off for Italy.

Finally, on Monday the snow cleared. It was brilliant sunshine outside, and the ice was beginning to melt. Now would come the fun part. We put our thermals on as even the 'warm' parts were only +1 degree, and left the refuge, hoping the tales of 20-degree sunshine down in the valley were true. It took a few miles until I was confident the road was dry, and then the real fun began. I knew the Morini's capabilities were way beyond mine, but that helped as I knew that so long as I didn't push myself too hard, the bike would stay true. As I became surer of the bike and myself, I began to ride faster, braking later and leaning it into corners with more and more confidence.

Of course, I will never be a racer - dad and Andy were always miles in front of me, but the important thing is that I was riding roads of the like I'd never seen before, on a bike I was largely unfamiliar with. I was improving all the time, and the Morini seemed to just go wherever I wanted it to. No matter how I drove it, the bike was always completely sure-footed. Proper Italian pizza in Cortina was fantastic, and the famous Ice man exhibition in Bolzano gave an outlet to culture.

Two days of hills, hairpins and straights. Bliss. But it had to end Wednesday morning as I was due to Start University on the Saturday. We woke up to a bright glowing from outside the window. Were we lucky or what? The previous evening had been dull, and we'd expected snow or at least rain. To our horror, the glowing turned out to be reflection off the soft white snow that had fallen overnight. As I remembered from before, coming down icy slopes was much worse than going up. A trouble-free 15Km later and dad and I were once again on the Brenner pass, bikes pointed in the direction of England with the intention of driving till our bums could take it no more. At about 7pm we arrived in Annweiler in Germany, just across the border from France. It was piddling down again and we were wet, bedraggled and happy to stop. Not a bad days riding, so we decided to call it quits there. 180-DM (£60) got the pair of us a fantastic meal and very comfortable room with a remarkable Breakfast.

Thursday morning we set off on the homeward straight. It was again pouring down and in the rush to get going Dad made a mistake fitting his panniers. Onto the Autobahn and head for France. We had not gone 50 km when a massive object flew off Dad's Vincent, and went bouncing across the road. Narrowly avoiding it, I did my best emergency stop and pulled in to the hard shoulder. Dad hadn't noticed and so continued up the road. I recovered the pannier; slightly chipped, but remarkably intact and waited until a rather concerned looking Arthur came trundling the wrong way down the hard shoulder. He hadn't noticed the pannier was missing and obviously thought I'd dropped the Morini. The look on his face when he saw me clutching his luggage!

Back on the road, wind it up to 85 and don't stop till we run out of fuel. Well that was the plan anyway. Passing a Verdun service station at 2 PM and the Vincent begins to slow down. The biggest plume of smoke comes pouring out of the exhaust. Terminal engine failure. (Holed piston caused by huge amount of water in the front carb which caused it to run very weak, but not misfire)

After spending nearly 4 hours trying to explain (in our best Anglo-French of course) to the French recovery service that "La Moto is old et cannot be fixed sans special parts," we finally got the bike onto a recovery lorry. The rest of the trip I would spend following a rented Fiat Punto. Why is it that when you're abroad and haven't a clue where you're going everybody seems to drive silver Fiat Puntos?

Completely fed up and a little de-moralised we pressed on, caning the arses off the Fiat and Morini so we could get as close to home as possible. It began to rain heavily. Double-speed windscreen wipers and turn the heater up for dad. (Tom never knew about the additional comfort of Radio 4, surprisingly well received in this part of France - Dad) Grin and bear it for me, straight through several thunderstorms of the "forked" variety. Apart from fuel we didn't stop again that day, and at 10pm we rolled into Calais, tired and wet. This time, however we had a guaranteed bed for the night, as dad had rung a French speaking mate in the UK who found and booked us into a hotel.

Dad's dead bike arrived in Calais at 14.00 on Friday, and we caught the first ferry home. Back in England and I felt like a god. I had driven the continent in the worst weather I'd ever seen. My Morini was still in one piece, and I'd have some great photos to show my mates.

15 riding hours Italy to Calais isn't at all bad and the trip was thoroughly enjoyable, despite not going entirely to plan (what Trans-continental motorcycle journey does?) It did however prove a few things. Just after I bought the Dart, I thought I'd made a real mistake. Bad reputation as "only half a Morini" and an insurance quote £500 more than an older 3 ½ made me feel less than happy about my purchase. However, the Dart excelled itself in every single way possible. It was more than capable of keeping up with dad's Vincent (old, but still seriously fast) and it also coped extremely well with the long, fast journeys we were doing. It proved to handle supremely in the Dolomites.

I know I knocked the emissions junk at the start of the letter, but I now see it as a complete package, rather than a pointless add-on. When I checked the oil in Italy, not only had the bike used virtually none, but also it was so clear that I couldn't see where it was on the dipstick. Moreover, we had noticed how little fuel the Morini was getting through compared to the Vincent, so on a motorway stretch in France, we both filled up and measured fuel consumption over the next hundred miles (bearing in mind this is at a constant 80/85 mph.) Whilst dad's bike returned a fairly respectable 40mpg, the Dart returned an absolutely phenomenal 81mpg!

The Dart really is an under-rated machine. It may not be a true Morini ("the poor outcome of Cagiva taking over," as the official Morini website puts it) but in my opinion it is the brilliant combination of Morini V-twin engine, modern chassis and reliability that makes the Dart's reputation somewhat unjust.

If you've got a Morini, then turn up to Morini club meetings or Cadwell Park. Go to Tescos on it if you like. Just use the thing and have some fun! I've only had mine a few months and already I've been to Italy and back. I'm not saying you should all go to that extreme, but I do think that we, as a club, need to promote the marque in motorcycling circles. Do we want the name Morini to die, or should it be recognised as once a small manufacturer of legendary race and road bikes?

Desert racing with Morini

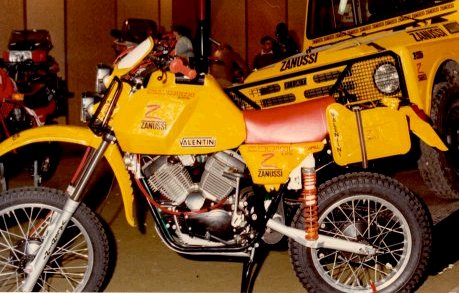

I found these pictures when I was searching for info on Valentini.

Valentini used to produce tuning parts for Morinis.

Above: A Zanussi sponsored Valentini prepared Morini and Land Rover.

No indication which rally these were prepared for.

Above: A cutting from a French paper. This is not a Valentini prepared Morini but it was ridden by a Massimiliano Valentini. According to the text he is on an official factory Morini. Again there is no mention of which year or rally this was, but Morini riders finished 4th and 6th. When I get time I will try to translate it into English.

Above: a cutting from a Spanish paper. Not sure what this is about, anyone out there care to translate it for me??

Morini 500 Turbo, First published in Bike magazine, June 1982

Throughout last year the residents of a quiet Bologna suburb were regularly treated to the sight and sound of a scruffy black Morini V twin growling along their streets to and from nearby dual carriageways. It obviously wasn't just another 500cc prototype - its motor appeared to breathe through a collection of washing machine parts, the steering head was loaded with dials and controls, and the tester riding it occasionally fiddled with various knobs on a small electronic control box. Had those same residents visited the Milan motorcycle show last November, it's likely they'd have failed to make any connection between the slickly finished machine grabbing all the attention on the Morini stand and that ratty test bike tooling up and down the Via Alfredo Bergami back home in Bologna. Except that both bikes had Turbo written on their side panels.

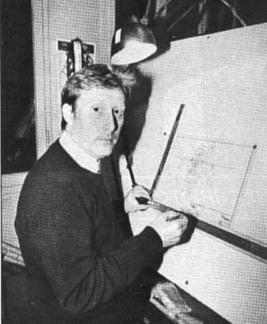

Morini, the smallest of the Italian motorcycle manufacturers making its own motors, just had to be the least likely candidates for the title of First Non Japanese Production Turbo Makers. Committed to moderate production of a standard range of machines of no more than half-litre capacity, using 72 degree V twin motors and a single-pot derivative, the little Bologna factory's philosophy hardly included assaulting the problem-strewn heights of turbocharging - let alone turbocharging a V twin; something supposedly so difficult Honda only did it to show off. Yet the decisions which sent Morini down Turbo Road were taken nearly 10 years ago. In 1973, soon after the introduction of the 350cc Sport, Moto Morini began looking at what to do next.

The Sport itself, designed by former Ferrari engineer and designer Franco Lambertini (left), was introduced in response to the changing world market for motorcycles. The Italian industry saw the writing go up on the wall in large Japanese characters during the late '60s. Morini, having been bombed out in 1943, built a steady base by meeting Europe's post-war demand for small motorcycles with a series of 98cc-250cc four strokes.

Convinced that they'd be unable to continue for long in the face of Oriental competition, Morini and the other Italian marques decided to move into areas where the Japs couldn't or hadn't the technology to compete - exclusivity and handling. Laverda went for superberserk megamuscle triples, Ducati brought out its refined and esoteric 90' V twins, Moto Guzzi did its best with its antiquated transverse V twin, shaft-driven motor. Only Benelli (under Alessandro de Tomaso) tried to take on the Japanese on their own ground with a never-very successful range of fours and sixes.

Morini's founder, Alfonso Morini, died in 1969 and the business was taken over by his daughter Gabriella. Two years later the first Morini V twin appeared.

At the time, it was an ideal move. The company now had a sporty (read 'satisfyingly loud'), slim, nice handling machine with an instantly identifiable powerplant, production of which was easily within the capacity of its small factory. Add a 125cc single (effectively a V motor with one pot lopped off), a 250cc twin for rich kids in the home market and a 500cc V for overseas and their short-term future was assured. So far so good. Morini's thinking from this point on was influenced by several factors. For one thing, three-quarters of its production goes to the home market where anything larger than 380cc has got to be pretty exciting to sell well because of Italy's infamous 35 per cent VAT loading on bikes over that capacity. Morini were determined to stick with the 72 degree motor which had become their trademark but at the same time it was clear that hogging Lambertini's design out to 500cc for the Maestro was pushing its ability to produce horsepower in the required amounts.

In any case, the company whose early 175cc four stroke sportsters gave Agostini a racing start in life harboured a deep rooted antipathy towards what the Italians quaintly term maxi motos. In Morini's view, increasing engine capacity and therefore mass to gain horsepower is a route which quickly runs into the law of diminishing returns; power to weight ratios improve sure enough, but rarely fast enough to match the weight increase, while the hassle of noise and emission regulations is something a small factory can well do without. They even produced a chart to back up the decision to opt for turbocharging. Claiming to show the general trend in maxi moto from 1973 to this year, it plots a rise in big bore output from around 70bhp to nearly 100, or a 30 percent increase. At the same time big bikes have become about 16 per cent heavier as a rule, say Morini. The crunch comes when you do the sums and find power to weight ratios on the biggest multis have only improved by 11 per cent (not to mention the fact that Alfonso Morini would turn in his grave at the thought of a 550lb Morini hitting the streets).

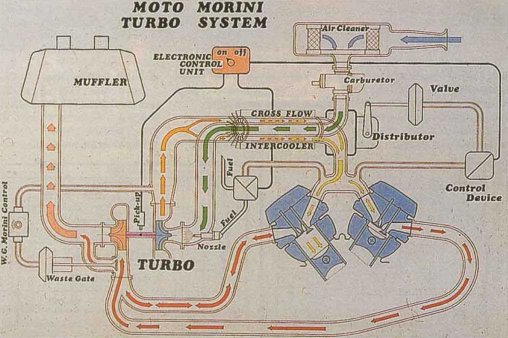

Looking at conventional solutions lead the company up blind alleys for three years. Until it considered turbocharging there didn't seem to be any way of making an acceptably fast yet light medium capacity machine without designing a new motor. And re-tooling to do that would have affected the whole range. In 1976 Morini finally decided to go for a turbo, aiming for 750cc performance from their existing 500cc powerplant with similar fuel consumption and little more weight than the standard bike. It was an ambitious project not least because the only turbos available at the time were almost useless on engines smaller than two litres but five years later they had their 500 Turbo. At least it looked as though they had. The pre-production model on show at Milan was strikingly different from any previous Morini but so well hidden behind the bodywork was the rear of the motor that it really could have had a washing machine in there. Only clue to its internals was an incomprehensible full colour diagram laying bare the baffling complexities of the Moto Morini Turbo System.

Closer investigation was impossible with dozens of Milanese pressing in for a better look and the sensible thing to do seemed to go back to the factory some other time. Which is why I was crawling through Bologna a few months later, nursing a hired Fiat 127 through the traffic and mentally composing a book entitled 101 Uses For A Dead Heathrow Baggage Handler. Yup, on strike again for an increased Smarties allowance or something.

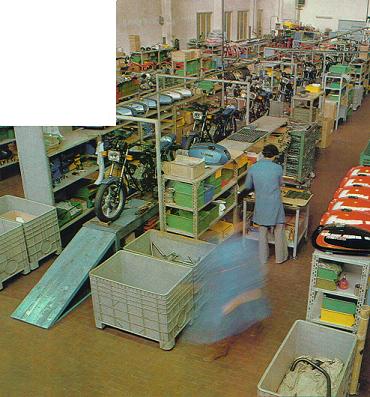

The Morini factory is a surprisingly small concrete building hemmed in on all sides by apartment blocks. Its small entrance hall holds a display of racing machinery from the '50s and '60s plus examples of the current range of models. Design and admin offices occupy the frontage, while assembly and machining are in the main body of the building, and rolling road testing, final checking and despatch are in the basement.

Morini factory employees move faster than the speed of light. This is the final assembly area. (Note the red and black 500 SEI-V tanks and the blue Strada tanks)

After being introduced to Morini's director Gianni Marchetti, Jim Forrest and I were shown round the works before being ushered into the Holy of Holies, the development workshop. If Honda allows two per cent of its annual budget to R&D, Morini allows about two per cent of its space. The workshop was about the size of a Jap R&D department's executive washroom although it was obviously ample for the factory's needs, with a ramp leading down to a dyno room in the basement.

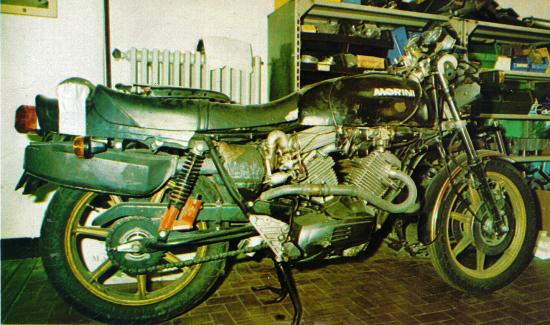

The Milan Show turbo was on a bench in the centre of the room, stripped of its bodywork and turbo gear. Resting on the floor was a horrible, battered object which was none other than the original prototype - now completely knackered after two years and 110,000km of road testing round the city.

Above: The actual development hack 500 Turbo - a far cry from the beautiful vision of the designers.

If it hadn't been for Big Four interest in turbocharging, which undoubtedly preceded the introduction of really small turbines, the Morini project might still be waiting in the wings. Last November Morini still hoped to find a home grown item for production turbos but it hasn't materialised and a Japanese IHI unit similar to those used in the Oriental boosters will sit behind the rear cylinder when the Italian turbo arrives in the showrooms. Having found their turbocharger, Morini still had a bundle of problems to overcome. The two main ones were getting a turbo system to work adequately given the uneven exhaust pulses of a V twin, particularly at low rpm, and secondly Lambertini and his development engineers Paolo Zaghi and Luciano Negroni had to devise special methods of keeping the cylinders cool while all those hot, compressed gases were being stuffed back into them. Honda, you'll remember, tackled the first of these problems with a complex system of electronic controls, fuel injection and a plenum chamber. Morini's solution was far simpler simply cut the turbo out of the system at low revs and feed mixture directly from a single 36mm Dellorto carburettor into the inlets

Simple though it sounds in principle, in practise the Morini system calls for a distributor between the turbine and inlets to direct the mixture flow. This was designed and placed at the end of an intercooler between the turbo and the cylinder heads. At low rpm the distributor closes the mouth of the intercooler and mixture flows across it into the motor. Exhaust gases still spin the turbine but the compressor on the other end of the shaft just pumps the same captive charge of air round inside the intercooler.

When the revs rise higher than a couple of thousand, sensors measuring depression in the inlet manifold tell the electronic control units it's time to operate the distributor, which opens the intercooler. Mixture is diverted down its centre to the compressor, then pushed up the outside to the inlets. To avoid momentary fuel starvation as the air already in the intercooler is stuffed into the motor, a small injector nozzle working on pressure from the head of fuel in the tank squirts juice into the compressor vanes.

The first prototype featured a fully adjustable distributor control on the steering head which allowed Morini to find the optimum revs for the change from normal to boosted breathing. Once they'd sorted this out, there was still the problem of greatly increased heat to overcome. In the faint hope that the Universe still contains any sentient beings not already bored to tears by the theory of turbocharging, I'll briefly re-iterate the sordid details.

A conventional internal combustion engine is both limited and fairly wasteful. It's limited by the ability of atmospheric pressure to fill its cylinders during the intake cycle, then it just pours about 35 per cent of the energy it produces during combustion away down the exhausts in the form of heat and gas momentum. The function of a turbocharger is to harness some of this wasted energy by making it spin a turbine which in turn spins a compressor which stuffs much more mixture into the pots than atmospheric pressure could manage. The result is, say, a 500cc motor which fills up with as much gas as a 750 or 900 and puts out equivalent power and torque. All you have to do is make sure it breathes properly and doesn't suffer from detonation, seizures, melted plugs or any other penalties of overheating.

Cooling the twin-pot mill presented Morini with a major headache, especially as the rear pot is partially masked by the front cylinder. Watercooling was out from the start: the prime reason for adopting turbocharging was to end up with a bike which made the maximum extra power for the minimum additional weight and bulk.

Schematic diagram is Morini's own, showing the importance of the intercooler

So an intercooler was designed into the system from the outset. Made, like all the turbocharging hardware on the bike except for the turbine unit, by Morini, the intercooler is really a simple heat exchanger. Fresh (cool) mixture is ducted down the centre and the hot - around 700'C at max turbine revs - compressed mixture travels up the outside losing heat to the incoming mixture and through fins on the intercooler body. It's a crude system compared to some of the latest car turbos which actually have a refridgeration unit, but it's the only intercooler on a turbo motorcycle.

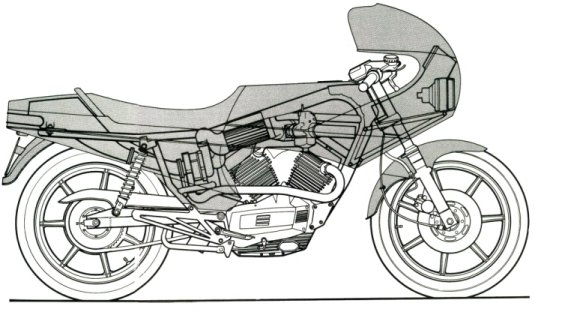

Cooling the charge also increases its density, making for better burning and less risk of detonation. The intercooler is hidden behind the sidepanels for the sake of neatness which begs the question of what cools the intercooler? The answer is that the eight-piece glassfibre fairing/ body unit isn't there just to make the Morini Turbo look decorative at garage parties. When Franco Marienotti at RG Studies was given a design brief for the superstructure, it included a stipulation that the lower section must function as part of the cooling system by directing air over the cylinder heads and boosting bitz. So twin scoops were placed either side of the single front downtube; the right one sending air over the front cylinder head, inlet manifold and intercooler and the other sending air over an oil cooler lying almost horizontally in the opening. A vent between the cylinders spills air on to the rear head while foils on the side panels turn a cooling breeze on to the rear barrel.

Yet more scoops on the side panels are supposed to cool the turbo and a large exhaust collector/silencer cradled in a frame extension under the tail. All this hot air exits through a slatted vent on the tail.

Aerodynamic considerations also played a part in the fairing design. It's often said that your average, unfaired motorcycle is an aerodynamically perfect as a flying brick. Unfortunately, faired motorcycles are not necessarily much better. Parting the air in front of the machine is less than half the battle because it's the drag and turbulence around the rear end and in the bike's wake which does most of the damage. As the airflow breaks up over the bike and rider it creates an area of low pressure holding the machine back, soaking up horse-power which ought to be making it go faster.

Morini's half-fairing is nowhere near perfect but they say the Suzuki RG500-style tail and through-flow of air reduce drag, while the blending of fairing and petrol tank at the front gets rid of unwanted turbulence behind the screen, which is where the air intake for the carb is situated. The crucial factor in top speed though is still weight. There's still one more unique feature on the Morini turbo. A wastegate control. Lambertini was not content with a conventional spring- loaded wastegate which opens when exhaust pressure reaches a pre-set level and bleeds off the excess, thus limiting turbine speed and so preventing boost rising to dangerous levels. So yet another electromechanical control was added.

Taking its instructions from pressure in the outlet side of the compressor venturi, the wastegate control lets boost pressure rise to nearly 18psi as the motor spins to 5500rpm before operating the wastegate, causing boost pressure to fall rapidly and level off at 12psi when 7000rpm is reached. From 2000 engine revolutions, cracking the throttle open spins the turbo to maximum boost in 1 1/2 seconds. Then the controlled opening of the wastegate cuts boost by 30 per cent.

Morini haven't fully explained the reasons for this but it seems the wastegate control makes plenty of boost available in the mid-range for 60-70mph cruising and rapid acceleration but reduces the pressure at high rpm before the volume of hot gas becomes too great for the elementary cooling arrangements to deal with. If the dyno charts I was given are to be believed this doesn't hurt power delivery, which climbs smoothly to its peak of a claimed 70bhp (at the gearbox sprocket) at 8500rpm - 1000rpm higher than the peak power point on the standard 500.

After five years' development and two years' road-testing, Morini appear to have come pretty close to the target they set themselves. If that 70bhp claim is the truth, they've extracted a 70 per cent power increase at the,cost of only 10 per cent more weight - the 183kg (403lb) turbo is 16kg (35lb) heavier than the latest standard 500.

Unfortunately, Morini won't let anyone ride their turbo yet. In any case, when I visited the factory only two Morini turbos existed: one of those was utterly knackered and the other was in bits. It'll be interesting to see how well all the mechanical controls work. Can that complicated arrangement of valves diverting mixture round the system make the Morini as smooth and well mannered on the road as Honda's computerised fuel injection? A bike which matches the Honda Turbo's smoothness and handling while giving its rider 120 fewer pounds to haul around would certainly be worth all that effort.

If it lives up to the manufacturer's claims it'll be at least as fast as the Honda Turbo at 210 - 215kph (130-133mph) flat out, and purportedly infinitely less thirsty at 55mpg overall going up to 60mpg at steady round-town speeds.

According to Negroni there's little noticeable 'turbo lag' because the intercooler distributor switch allows a head of pressure to build up and come in with a bang when it goes over to boost. When I was in Milan last year, however, Paolo Zaghi said the switch operated at 4000rpm. if that's correct then you'd expect the motor to be struggling a little as the 8.6:1 compression pistons (as opposed to 11.2:1 in the standard mill) sucked mixture through the single carb, long inlet manifold and round the sharp bends into the Heron heads.

Yet Morini's dyno charts claim a 10 per cent increase over power at four grand ... some mistake there, surely. Or maybe it's my total ignorance of Italian.

Most of the scepticism which has greeted the turbo stems from the few changes Morini have made to the 500's internals. It runs a stock crank but the low compression pistons are forged. Only other change specifically related to turbocharging is a beefed-up version of the two-plate dry clutch, though the factory has finally broken with tradition and linked the gear selector to a left foot lever. A sixth ratio has been added to the gearbox as well - both these mods appearing on the latest export versions of the 500.

To be fair, turbocharging doesn't increase mechanical loads on the bottom half of the motor, in fact the softer compression reduces the hammering, though the whole transmission has to relay far more power to the rear wheel. Nor does moving the power peak 1000rpm higher come near the very high revs which racing Morini big ends were asked (but failed) to cope with in the Island some years back.

Those forged pistons are there because thermal loads on the top half of the motor are so much higher than in a conventional motor and it's this problem of cooling which is more likely to cause failures than mechanical stresses.

Morini aroused scepticism as much by the way they quietly sprang the bike on a surprised world at the Milan Show as anything else. The Japanese have never bothered to explain just why they'd tackled turbocharging - Honda's attitude seemed to mirror the old Everest climbers' answers: 'Well, we did it because it was there,' and none of the machines so far offered to the press come near to achieving the supposed target of markedly improved performance for minimum cost in weight and fuel consumption. The CX500T ended up weighing more than the 900 four it was supposed to make obsolete but couldn't better it on top speed, fuel consumption (even though the CB900 is appallingly thirsty anyway) or overall acceleration.

This hasn't stopped the Oriental turbos receiving so much hype overkill it's hard to decide whether they're going to save the world or bring civilisation as we know it to an end. Then a little Italian factory whose fanatical devotees insist on light, easily serviceable, nimble motorcycles has the outrageous cheek to produce a neatly integrated turbo which, on paper at least, comes nearer to delivering the goods than any other save that developed by mighty Yamaha.

But Gianni Marchetti doesn't see Morini's arrival on the booster scene as having anything to do with muscle-flexing or joining the tailchase Honda started with their turbo. Morini has been at pains to point out that it started developing its turbo in 1976 and it's possible that if the company had had the clout to persuade a European manufacturer to develop a suitably small turbocharger a few years ago it might have had the world's first production turbocharged motorcycle in the shops.

The Bologna factory decided long ago that there was sufficient demand for 120mph-plus machines to make it worth developing one of their own. Alongside the turbo, Lambertini drew up designs for a 650cc Maestro (the Misstro?) and experimented with different head designs - conceivably we might have been offered something like a 72 degree version of the Ducati Pantah - but those designs are still on the shelf.

Look at it another way. Morini has neither the desire nor the resources to make large, heavy machines. In Marchetti's view, the cash spent on meeting increasingly restrictive noise and emission regulations, on the back-room political infighting leading up their introduction and on promotion in the dwindling marketplace would be good money thrown after bad. Or: there's no way 116 Italians can beat Hondawayamzuki.

If and when a few Monni turbos are delivered into the hands of the press for evaluation it'll be clear once and for all how well the factory's played its cards. Until then the cynics will continue to claim Morini is merely making a virtue out of a necessity, while more charitable individuals will no doubt reach for their paperback copies of Small Is Beautiful.

Talking of small, Morini decided several years ago that it needed to move out of the moped market. Now it's not so sure. One project which is nearly ready to go should the moment arise is a 50cc four-stroke motor. It'd be one hell of a follow-up to a 130mph turbo.

A long Ride South, David Minton

The red 500 Morini lay awaiting collection in the Flying Tiger's air freight depot in Anchorage, Alaska, on August 21, where it had been sent by the American West Coast distributors. I had requested a fully run-in tourer, and this one almost frightened me out of my socks because it was brand new. For all my apprehension, it fired up first go and ran me around Anchorage in perfect humour during the last day's shopping and packing. On August 22 I turned east out of Anchorage and pushed into the wilderness along the glistening tarmac of the wet Glenn Highway. Rain drifted across the road like skeins of dirty silk. In high country thick mist wrapped everything in saturating intimacy. Ahead of the front wheel each rain drop exploded back upwards a couple of inches where it blended into a white-water swirl with its million neighbours. The swish of the wet drowned the sound of the exhaust. I sat like a lost dog in the rain. Occasionally the deluge eased a little as the weather took a deep breath, ready for another long, heavy squeeze. I saw distant mountains, huge rivers, white glaciers. The Morini sped on. Smack on the Canadian border the tarmac stopped, and the road south through Yukon took on most of the character of a British trials section - mud, mud, and more mud. The smoothly treaded touring tyres could barely cope and turned the ride into a wearying, seemingly endless struggle. The same mud encapsulated the engine and caused it to overheat, so every 50 miles I had to break it off with a tyre leaver. It got into every opening, every joint. Controls stiffened and jammed, my neck was sandpapered, my eyes watered red and sore, my mouth filled with a sooty, greasy grittyness. Mud coated the inside of my gloves, lubricated handlebar grips, jammed the camera, covered clean spare clothes, and eventually it penetrated into the starter motor clutch. Given that the little (how standards change over the years!) V twin was put to work in elements it was, arguably, never designed for, how did it cope? Briefly, exceedingly well. It logged 7000 miles between Anchorage and the south of Baja, Mexico. Apart from the starter clutch repairs in Vancouver, Canada (which could have been avoided had I known of the factory's advice to tape over the outer engine cover air vent for off-road riding) the only time a spanner gripped the bike in anger was during regular maintenance. Unending rain through Alaska. Mud, shale and rocks in Yukon and British Columbia. Maximum cruising speed through California, and long days of desert heat and rough riding in Baja. Despite this, the list of replacement parts is small, and amounted to a new rear tyre, chain and starter clutch shoes in Vancouver. Down America's beautiful Pacific Coast Highway the Morini responded to the element it was built for. That much I could feel as the compact 500 shook off the strange rigours of the previous 10 days and dived eagerly into the curlicues of that magnificent coast road as though back among the Dolomites of its home country. Despite eighty pounds of luggage the Morini heeled as fluidly and naturally around those bends as only an Italian machine can do these days. Straight lines it accepted with patience and dignity - bend it lived for! For the first time in 3,300 miles we travelled together as a single entity, Morini and I. Conscious effort disappeared. We untied the loose knots in that long and twisting road. We turned motion into poetry and sang the miles away. We felt the elastic grip of gravity and turned it into a partner. No blaring of angry revs, no jerking brakes, no worried handlebars or pedal-stamping feet. The road was to us what cliffs were to the seagulls. As they rode the salt breezes, so we rod the highway. Coastal mists and giant redwoods. The sound of the Pacific's great lungs. The eager bass babble of a living V twin. The fine rhythm of a travelling man. While I understand the nuts and bolts of machinery, and am aware of the necessity to take a detached point of view about everything concerned with selecting, buying, riding, maintaining and owning a motorcycle, I don't really give a tinker's cuss any more - not for myself, anyway. I want life, vitality, personality from a machine. I want an engine that sounds like an engine and not like a super modern motor. You know - bompa bompa bompa, not thrrrruuummmmmm… That ruddy starter clutch business drove me wild, but I'd accept it over and over again if it meant I could escape the cleverly camouflaged, thin-ice horrors of perfectly presented two-wheelers. Once over the border and into Baja, the temperature rose in direct inverse proportion to petrol quality. Pemex (an apt description if you care to juggle a while with the phonetic implications of the name) was generally available only in its 80 octane Nova rating. 95 octane Extra was rare. The Morini's Heron-type combustion chambers deserve their reputation for an ability to deal efficiently with poor fuel. Although a little over 11 atmospheres are squeezed into each combustion chamber "pinking" occurred on one occasion only. An interminably long incline and stiff head-wind proved too much for top gear to handle without the most abominable noises of protest from the octane-starved cylinders. The temperature was almost 130oF and the tyres were too hot to touch, but using fourth gear as the cruiser cured all problems and the Morini held a steady 65 mph without stress. Most evenings I searched out a small motel on the coast and feasted on fresh sea food for dinner and breakfast. At one of them I learned of a mission still being run by monks, and who would probably provide me with food and a bed. It was in the middle of the desert. After two hours of exhausting enduro-style riding through heat of killing intensity I found the mission, but it was deserted, apart from four filthy types who came running out, throwing large stones and beer cans. They shouted "Gringo, hey Gringo frien'". One waved a machete. They jumped into a battered old jeep and came after me. "Gringo, hey Gringo". Maybe they were starved of good conversation. Maybe they were holding a party. I flung the Morini out of the mission garden and up a seemingly impossibly steep and boulder strewn gradient that was the only way ahead. Praying that the high bottom gear would be able to cope I bashed and crashed up a path surfaced with rugby ball shaped boulders and three or four rock steps. Miraculously, the heavy tourer with its eight pounds of luggage bounced up, while the Jeep balked at the second rock step, transmission whining and tyres growling. Heat, nervous tension, and the sheer physical effort of "bossing" the Morini was within moments of knocking me out. My arms had almost locked up and my hands refused to grasp the handlebars firmly. Fifteen minutes on I collapsed in the deep, permanent shade of some low cliffs, head and heart pounding with a blinding jolting pain. On recovery I realised that I was lost, and learned from map and compass that I was facing due south and empty desert, rather than due west and the planned 20 miles only to the main road. After a nightmare journey of another three hours through temperatures that were so high my leathers' outer surface was too hot to touch, the main road showed up. There was more water in my emergency bottle than there was petrol in the Morini's tank. During those three hours my mind had refused to concentrate on anything but fantasies of cool water. It had been a bad time. The most astonishing aspect of the entire ride was the condition of the Morini which, was no different from that of a normal. The right tele-leg seal had given way during one of the numerous wallops it had been subjected to, but that was all. If nothing else, the experience proved that a desperately ridden good two-wheeler will outstrip a drunkenly driven worn-out four-wheeler across rugged country - given a large slice of luck, of course. In fairness to the people of Baja, it should be explained that this single incident contrasted strangely with the kind hospitality evident elsewhere. During the entire trip the Morini covered a little under 7000 miles, including 1000 miles of unpaved road. On more leisurely days it was usual to turn in around 74 mpg. Main highway cruising at a steady 80 mph returned 60 mpg, but while the machine was manifestly mechanically capable of withstanding a flat-out cruising speed indefinitely, as petrol consumption rose to 48 mph it was rarely maintained. Top speed at the end of the ride was a true 90 mph with all luggage equipment aboard and me sitting bolt upright. If the machine was stripped and I lay prone it rose to a creditable 102 mph. During the final inspection the valve clearances were found to have widened, the rear sprocket teeth hooked, the rear light filament broken, and paint had been abraded from some luggage and rider-rubbed high spots. There were no oil leaks, and none had been burned. The entire electrical system functioned correctly. Nothing had shaken loose, dropped off or fractured. The proof of real satisfaction with anything lies in the answer you might give to the simple question: "Would you do it all over again, the same way, with nothing changed?" I would, although with the single proviso of a decent seat - the standard Morini thing is an instrument of the most excruciating torture. One amusing incident brought home just how futile it is trying to explain to people who are stuffed up with their own preconceptions, the quality of less well-known machines. As I pulled into a California roadhouse for lunch, members of a Gold Wing touring club crowded around, none of whom knew the first thing about Morinis, but every one of whom advised me of its total unsuitability for such a long and rough trip. Too small, too fragile, insufficiently powerful, and potentially unreliable was the consensus of group opinion. They left before me. An hour down the road I overtook them. By sheer coincidence, hours later, they stopped overnight at the motel I had booked into. This time they lectured me on the immorality of high speed cruising…… DAVID MINTON

DECEMBER 1980